App Concept: How can we help our visually impaired friends?

13 February 2021

Walking on pedestrian paths is something everyone needs to do, for basic commute. Pedestrian paths are a lot safer than walking on grass plains or even on the roads. However, all kinds of dangers can still lie within the walking boundaries of the paths.

Small tripping hazards such as unevenly laid out pathways or litter, or the larger moving hazards, mostly fueled by inconsideration, like when people walking while on their mobile phones, or an inconsiderate bicycle rider riding at high speeds, are all hazards for any pedestrian.

The issue is amplified even further, when the pedestrian is visually impaired. They might not be able to fully sense the impending danger. While one could potentially use a walking stick to sense the small tripping hazards, the walking stick cannot serve as a good indicator for the visually impaired pedestrian to sense if there’s an incoming larger hazard, such as a bicycle, especially when the area is particularly noisy, hiding the noise generated from the wheels and friction of the bicycle.

Trouble!

Imagine this: An impatient, inconsiderate and reckless cyclist is riding on a bicycle at blazing fast speeds. The cyclist, unwilling to lose momentum, is expecting everyone to stay clear of said cyclist’s track, on the public pedestrian paths, next to a noisy construction site nearby.

The cyclist thinks: "the pedestrians that sees my bicycle, would, without a doubt, give way, since it's travelling so fast. Nothing to fear."

This poses a serious threat to the visually impaired pedestrian, on the same path, as the noise from the construction site might have covered the noise from the bicycle’s wheels. When the cyclist sees that the pedestrian did not move away, it is likely too late, as it's unlikely that the cyclist could stop in time, since, it takes effort to fully stop, especially when travelling at high speeds.

The risk of a collision is very high at this point, and the injuries that could be sustained by both parties could be severe, due to the speeds.

Of course, not all cyclists are such cyclists, and most are responsible riders.

There could also be a case where the walking stick might poses more as a trouble than an aid. The walking stick, also known as a white cane, helps visually impaired persons by feeling their surroundings to identify potential obstacles.

However, as good as it is, it has been reported from those who uses it, that they may accidentally tap nearby people, sometimes to the extent of tripping others.

While the victims will sympathetically and understandingly forgive the visually impaired person, there could be possibilities where, instead of tapping on someone else, there could also be the case, where the person accidentally taps on an animal. That could be dangerous.

There is occasionally wildlife roaming about, even in urban areas, with animals such as wild boars, stray cats, dogs and monkeys, on the streets. There could be the case where the visually impaired person might not have felt the presence of such wildlife and may inevitably tap the animal with the walking stick, causing the animal to react aggressively. The animal will perceive this as an act of provocation, causing harm to the person.

These are all scenes that we wish to never see occur on any one.

A lot of the above scenarios can be avoided, when members of the society step in and help the visually impaired persons. However, they might still be at risk of danger, as its impossible to have people at every place, at every time.

This put us, as a team of student mobile software developers to start thinking and imagining, what could we theoretically do, to make our visually impaired friends go anywhere they want, safer?

What can we do?

We looked at our own phones. What are their capabilities? What sensors does it have? And we thought of using LiDAR sensors. Brilliant Cameras. Accelerometers. Artificial Intelligence. Object Recognition.

All kinds of technology flowed into our imaginations, and with it, came an idea.

Our Idea!

The idea we have, is an app. This app will be one that utilizes a set of technologies on a smart phone, to communicate with visually impaired persons about potential moving threats and risks, based on the situation in front of the smart phone. The smart phone essentially tries its best to ‘sense’ what’s in front of it, with the Artificial Intelligence, to identify the possible threats.

The technology

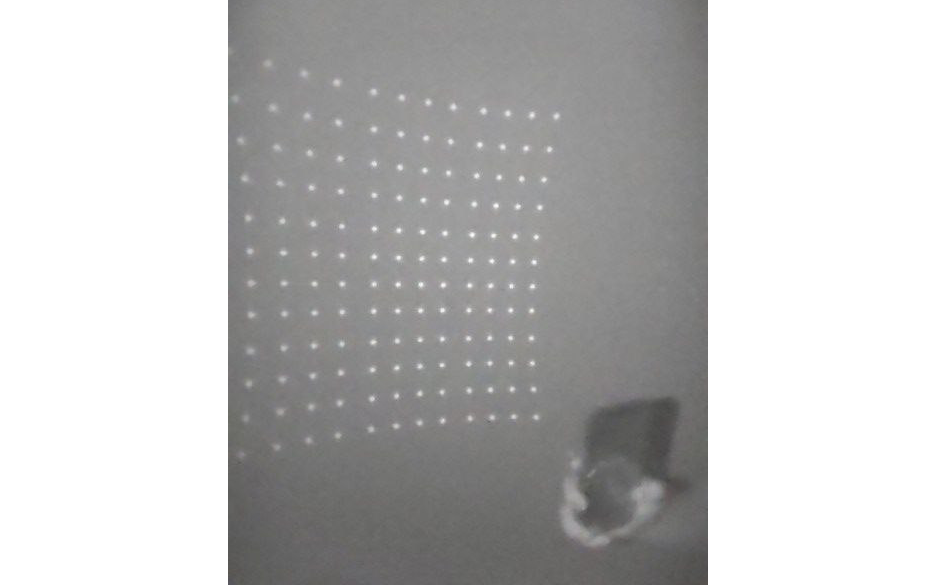

The app will use LiDAR sensors when possible, which provides up to about 5m of depth sensing, with imagery (from cameras) and algorithms to measure distance, and speeds. We also thought that, if possible, we could also perhaps use the multi camera setup for better movement sensing.

Look! It's the LiDAR sensor of the iPhone 12 Pro Max at work, captured using an IR camera!

As LiDAR relies on Near Infrared (NIR) technologies, not Ultraviolet (UV), it is likely a safe way to conduct depth sensing, even in dark places where cameras cannot see properly.

LiDAR works by projecting an array of lights on an object, and measures the timing it takes to reflect back, to estimate the distances, at a lightning-fast speed. This also meant that it will work in the dark, but fares poorly at transparent or translucent objects. Cameras bring us the best of both worlds though, as cameras can allow the app to 'sense' transparent/translucent objects better, by picking up glass/water reflections data.

The device’s accelerometer will also be used to detect potential falls of the user if it happens, as well as to cancel off potential misreading of the speed of the potentially threating object, and the user, whom might be moving.

This wide range of data, provided by an abundant of sensors, allows the app to measure distances, speeds, and predict what could happen and how to react, using Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The app uses all the above, to tell what’s in front, if it’s a threat, and how to help it’s users avoid danger.

How does it communicate though?

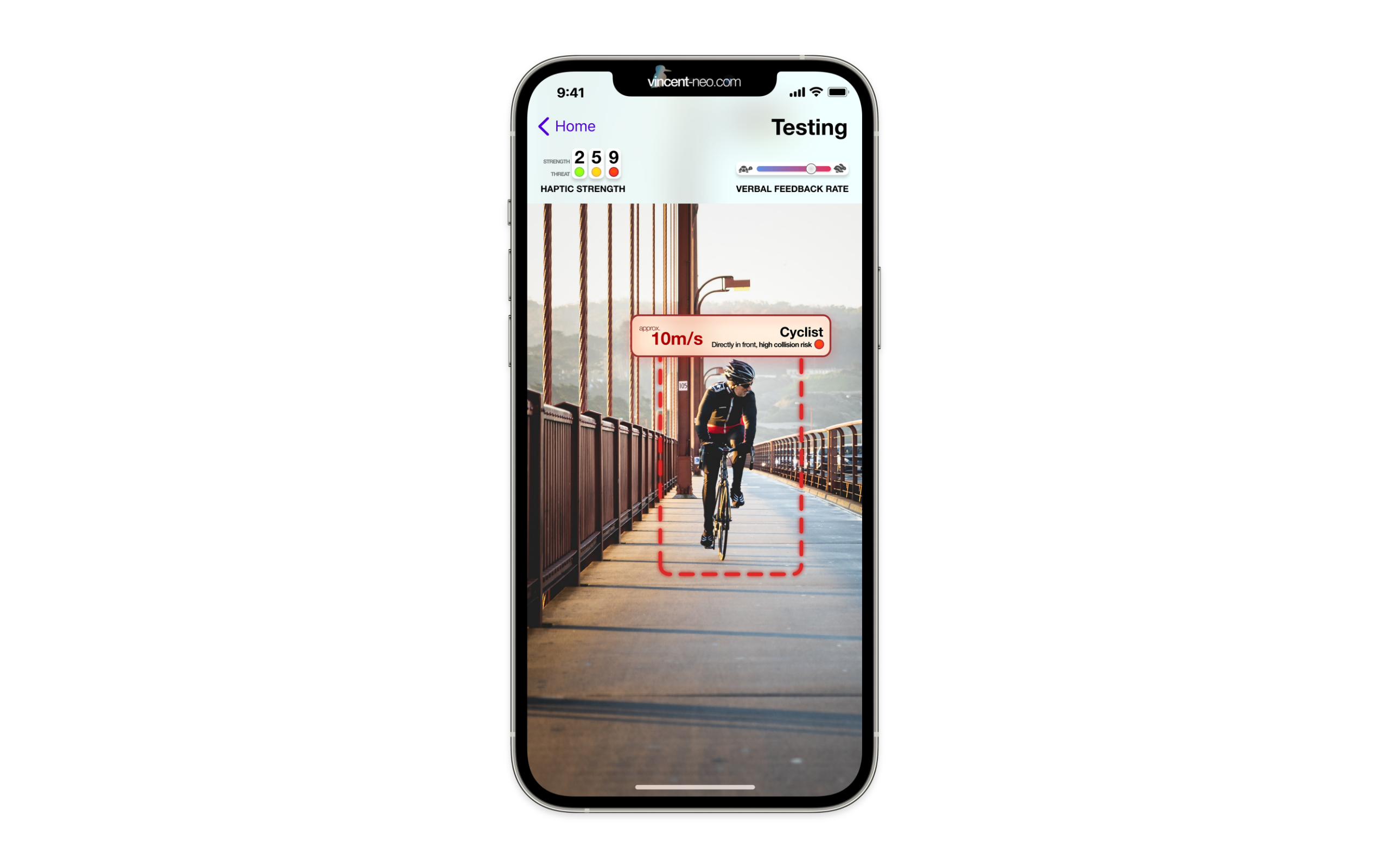

The app will also use haptics and verbal feedback technologies to communicate with the user. When a threat is detected, the app will try to determine a countermeasure, for the user. This is dependent on the object that is incoming, the potential risks, and the time to collision. The countermeasure is then spoken to the user as well as telling the user what’s in front. This allows our users to decide the best course of action to protect themselves.

Why haptic feedback too?

The time to collision variable is very important in this case, as there might be times where the collision could have occurred at a speed so fast, the countermeasure may not be communicated to the user fast enough to work. This is where haptics comes in. A caretaker could set the haptic level for the person, with different strengths for different threats. It only takes milliseconds for the haptic vibrator to vibrate, alerting the user of a potential risk.

The app may also be configured to flash the device’s flashlights, at night, to make the potential threats (such as other persons or cyclists, etc) aware of the person, and to knocking onto the visually impaired person.

What if...

In the case where the unfortunate scenario did happen, the app will use the accelerometer sensors of the device to detect a fall or impact. This allows for the app to decide for the user, what to do next. The app can be configured to call either the caretaker, or the emergency services, when it happens.

The app concept

The app will have two modes. A caretaker mode will allow the caretaker to seamlessly set up the app to best fit the visually impaired person. When done, the caretaker will lock the controls and it will be ready to deploy for the visually impaired person. The locking mechanism ensures that settings are not accidentally switched or turned off through accidental clicks.

Caretakers may test the configuration through the testing page of the caretaker mode. This feature aims to provide faith in the system, where they can test the accuracy of the detection, speed, as well as to test if the haptic strength and visual feedback rate is suitable.

The deployment mode will be the mode for the visually impaired person to use. The display of the device will be off in this mode. There should not be a need to interact with the device, so the user can choose to hang the mobile device on their neck or put it in a shirt pocket, with the camera units of the device facing forwards.

This mode can be deactivated by the caretaker when needed, through a triple tap and slide up gesture, and passcode.

For an example of a not dangerous situation, a bird could be flying right in front of the person, as it passes by. Our app may detect the bird and describes it to the user verbally. While it is unlikely that the bird could pose much of a threat to the person, it is likely good for the person to know, such as to move away, especially if the person dislike birds.

If we look back at the example scenario earlier, of the reckless cyclist travelling at super-fast speeds, if the pedestrian had the app of our idea, the phone will try to both verbally communicate to the pedestrian what’s in front, as well as a countermeasure (if time permits), and haptic feedback to alert the person. This should better allow for the user to know what’s happening and try to react it the situation.

What are the current options?

The purpose of the app is to help the visually impaired persons around us, and there may be many ways that can potentially help them, each with its own set of pros and cons. With that, there is indeed a couple of apps with a similar purpose, but with a different way of executing and functionality set differences.

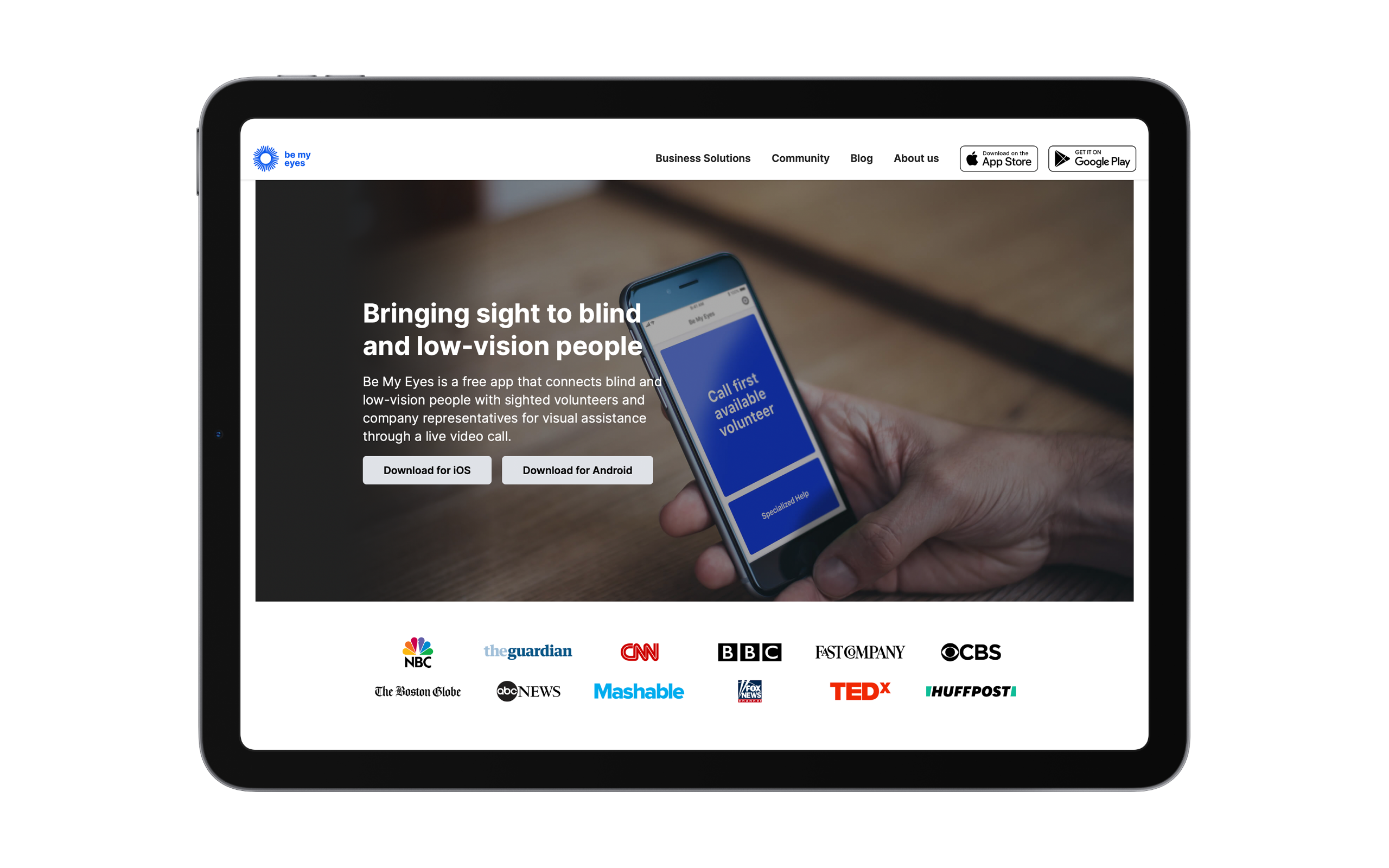

Be My Eyes

by Hans Jørgen Wiberg

This is a free app that links sighted volunteers to the visually impaired persons, where a video call allows for the volunteer to speak to the person in need, with the live video as a reference for the volunteer to help or explain. This helps the person with their everyday tasks, such as reading expiry dates, instructions, and more.

Strengths

- Free app with more than 4 million volunteers around the world

- Multi language support

- As the person offering help is another person, there is no fear towards incorrect detection that could be caused by Artificial Intelligence inaccuracies.

- Works on any phone – iOS or Android, no special hardware needed

Weaknesses

- Privacy concerns for the visually impaired person, as the volunteer is a complete stranger.

- If there are rogue volunteers, such as those that join for the purposes of mischief, it could pose a danger to the visually impaired user.

Opportunity

- Use of AI could be better for privacy as what is seen on camera is not seen by any randomly assigned person.

Threat

- Good natured volunteers will always be better than AI, at understanding things, explaining things, friendliness, etc.

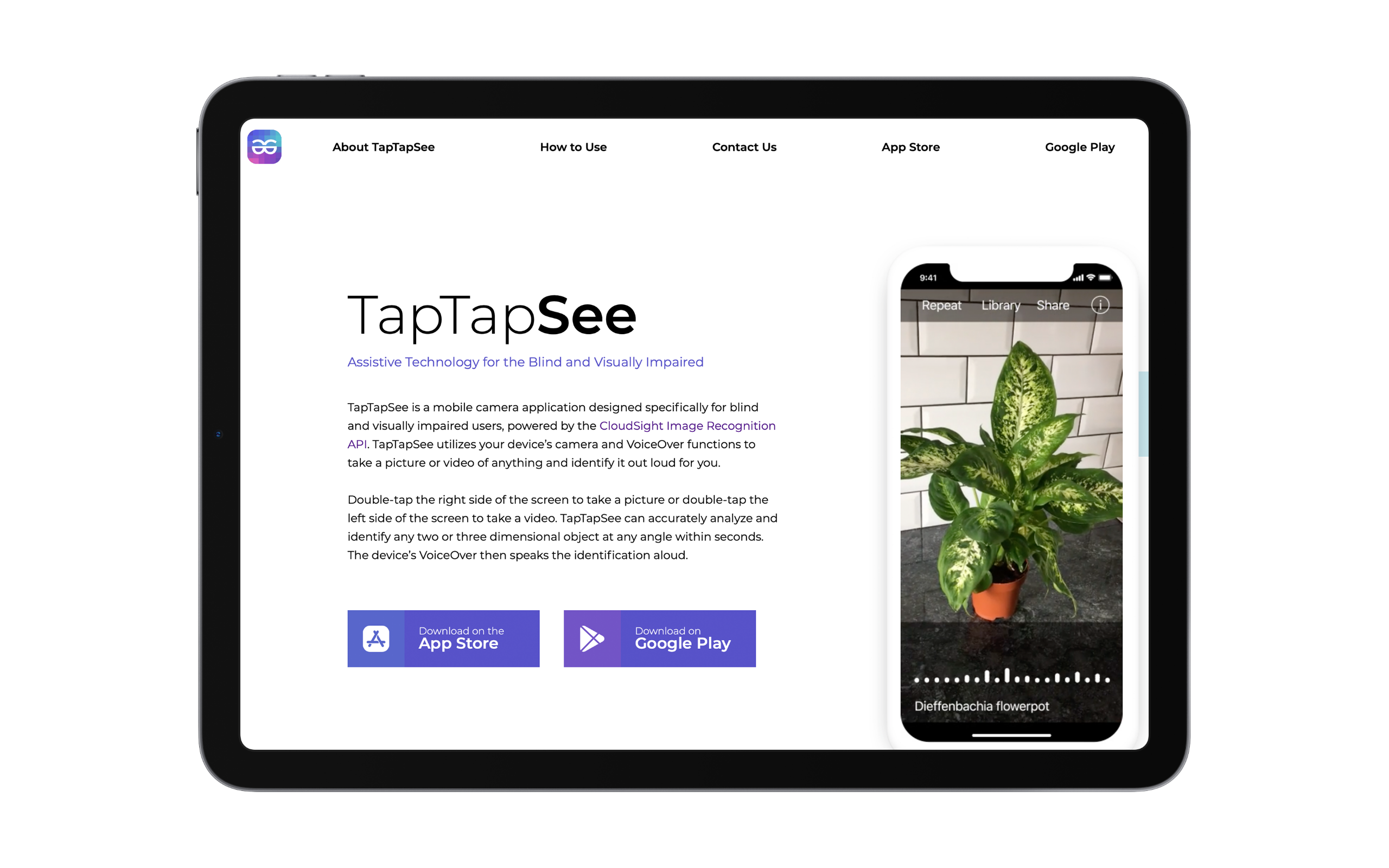

TapTapSee

by CloudSight Inc.

This app lets visually impaired users take images or short videos (up to 10s) of objects, to be sent to an image recognition cloud for processing, with a voice feedback of what the object is.

Strengths

- Uses AI image recognition technology, no need for volunteers.

- Verbal feedback of the analyzed item.

Weaknesses

- May take up to 7-10s for recognition cloud to return result of the identified object.

- Privacy Policy states that anonymized user data (such as submitted images or videos) captured from this program might be shared with external organizations such as third-party advertising partners.

Opportunities

- It will be better to offer a privacy policy that does not share user data out to external organizations.

- Faster detection. 7-10s delay, if used on our idea, would be too large of a delay to effectively avoid accidents.

Threat

- Their app could be further improved on with features that may resemble our ideas, as both builds on the use of AI technologies.

Conclusion

This is a team project concept by a group of Republic Polytechnic Mobile Software Development students, collectively imagined. We hope that our ideas will inspire others to build accessible software for everyone and thanks for reading!

References

Image used can be found in Pexels, a free-to-use stock image site.

Man Riding a Bicycle On Bridge By Craig Dennis

Seagulls Flying over Beach By Julia Kuzenkov

Attentive pedestrian with coffee and animal carrier walking on roadway By Sam Lion

Articles Referenced

Qing, A. (2020, November 20). Woman attacked by wild boar while exercising in Sungei Api Api Park. The Straits Times.

BBC News. (2015, November 18). How dangerous are white canes? BBC News.